Packet #1:

reading ::

Change By Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations

Change By Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation - Tim Brown

:: excerpts I found interesting:

The next generation of designers will need to be as comfortable in the boardroom as they are in the studio or the shop, and they will need to begin looking at every problem—from adult illiteracy to global warming—as a design problem.

I preach this in my classroom. I’m teaching a class this semester that tackles broader problems than my students are used to working with. They seem to be enjoying the process and have been very supportive of each other offering alternative ideas and expansions on old ideas.The tools of conventional market research can be useful in pointing toward incremental improvements, but they will never lead to those rule-breaking, game-changing, paradigm-shifting breakthroughs that leave us scratching our heads and wondering why nobody ever thought of them before. Our real goal, then, is not so much fulfilling manifest needs by creating a speedier printer or a more ergonomic keyboard; that’s the job of designers. It is helping people to articulate the latent needs they may not even know they have, and this is the challenge of design thinkers. How should we approach it? What tools do we have that can lead us from modest incremental changes to the leaps of insight that will redraw the map? ... I’ll call them insight, observation, and empathy.

Empathy is the mental habit that moves us beyond thinking of people as laboratory rats or standard deviations. If we are to “borrow” the lives of other people to inspire new ideas, we need to begin by recognizing that their seemingly inexplicable behaviors represent different strategies for coping with the confusing, complex, and contradictory world in which they live.

...their seemingly inexplicable behaviors...I see this every day for every day issues. Some folks could use a little help with their coping strategies. Myself included, I suppose.We are in the midst of a significant change in how we think about the role of consumers in the process of design and development. In the early years, companies would dream up new products and enlist armies of marketing experts and advertising professionals to sell them to people—often by exploiting their fears and vanities. Slowly this began to yield to a more nuanced approach that involved reaching out to people, observing their lives and experiences, and using those insights to inspire new ideas. Today, we are beginning to move beyond even this “ethnographic” model to approaches inspired and underpinned by new concepts and technologies.

For the moment, the greatest opportunity lies in the middle space between the twentieth-century idea that companies created new products and customers passively consumed them and the futuristic vision in which consumers will design everything they need for themselves. What lies in the middle is an enhanced level of collaboration between creators and consumers, a blurring of the boundaries at the level of both companies and individuals. Individuals, rather than allowing themselves to be stereotyped as “consumers,” “customers,” or “users,” can now think of themselves as active participants in the process of creation; organizations, by the same token, must become more comfortable with the erosion of the boundary between the proprietary and the public, between themselves and the people whose happiness, comfort, and welfare allow them to succeed.

Louis Pasteur observed in a famous lecture of 1854, “Chance only favors the prepared mind.”

Another line I can use with my students.

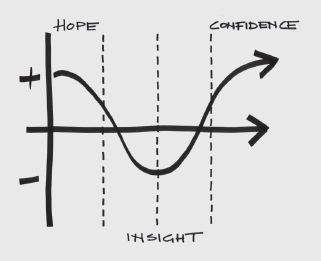

Design thinking is rarely a graceful leap from height to height; it tests our emotional constitution and challenges our collaborative skills, but it can reward perseverance with spectacular results.

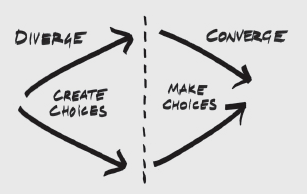

Others, less in awe of the cult of the designer, may confuse the mastery of tools—including the qualitative tools of brainstorming, visual thinking, and storytelling—with the ability to reach a design solution. And there are those who may feel that without a precise framework or methodology, they will be unable to fathom what is going on. They are the ones who are most likely to bail out when the morale of a team dips, as it invariably will over the life of a project. What they may not appreciate is that design thinking is neither art nor science nor religion. It is the capacity, ultimately, for integrative thinking.

Management at the University of Toronto, Roger Martin...in The Opposable Mind, based on more than fifty in-depth interviews, Martin argues that “thinkers who exploit opposing ideas to construct a new solution enjoy a built-in advantage over thinkers who can consider only one model at a time.” Integrative thinkers know how to widen the scope of issues salient to the problem. They resist the “either/or” in favor of the “both/and” and see nonlinear and multidirectional relationships as a source of inspiration, not contradiction. The most successful leaders, Martin finds, “embrace the mess.” They allow complexity to exist, at least as they search for solutions, because complexity is the most reliable source of creative opportunities. The traits of management leaders, in other words, match the traits I have ascribed to design thinkers. This is no coincidence, and it does not imply that the “opposable mind” is the reward to those who won the genetic lottery. The skills that make for a great design thinker—the ability to spot patterns in the mess of complex inputs; to synthesize new ideas from fragmented parts; to empathize with people different from ourselves—can all be learned.

So, if my house is a little cluttered, but through it I know where things are and am able to construct things from it, does that count?Actually, as I look at “the mess” around me socially and physically (inside and outside my personal world) I have to admit, it’s not easy to embrace. My natural inclination is to “fix it.”

Frank Lloyd Wright claimed that his early childhood experience with Froebel kindergarten blocks—developed by Friedrich Froebel in the 1830s to help children learn the principles of geometry—ignited his creative passion: “The maple-wood blocks…are in my fingers to this day,” he wrote in his autobiography. Charles and Ray Eames, one of the greatest prototyping teams of all times, used prototyping to explore and refine ideas, sometimes over many years. The result was nothing short of the reinvention of twentieth-century furniture. Asked by a curious admirer whether the iconic Eames lounge chair came to him in a flash, Charles replied, “Yes, sort of a thirty-year flash.”

I’m with Wright. As the oldest child in a neighborhood with no other children, I spent hours playing with things I found in the yard or in my mother’s kitchen and sewing kit. I made a log cabin with sticks (branches) from the yard. I used a round file to grind down notches so they’d fit together at the ends, glued them together, built little furniture out of scrap lumber from Dad’s garage, and added a little “bear” rug from some fuzzy fabric in Mom’s collection. Dad helped me build a roof and we glued the whole thing to a plywood base. It was much cooler than my Barbie house.The best and most successful experience brands have a number of things in common that may provide us with some secure guidelines. First, a successful experience requires active consumer participation. Second, a customer experience that feels authentic, genuine, and compelling is likely to be delivered by employees operating within an experience culture themselves. Third, every touchpoint must be executed with thoughtfulness and precision—experiences should be designed and engineered with the same attention to detail as a German car or a Swiss watch.

Mostly we rely on stories to put our ideas into context and give them meaning. It should be no surprise, then, that the human capacity for storytelling plays an important role in the intrinsically human-centered approach to problem solving, design thinking.

:: when the point of the story is the story ::

Design thinking can help bring new products to the world, but there are occasions when it is the story itself that is the final product—when the point is to introduce what the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins famously called a “meme,” a self-propagating idea that changes behavior, perceptions, or attitudes. In today’s noisy business environment, where top-down authority has become suspect and centralized administration is no longer sufficient, a transformative idea needs to diffuse on its own. If your employees or customers don’t understand where you are going, they will not be able to help you get there. This is doubly true in the case of technology companies and other businesses whose product may not be easily recognized or understood.

Businesses are taking a more human-centered approach because people’s expectations are evolving. Whether we find ourselves in the role of customer or client, patient or passenger, we are no longer content to be passive consumers at the far end of the industrial economy. For some this leads to a quest for more meaningful pursuits than “getting and spending.” For others it may take the form of holding companies accountable for the impact of their products upon our bodies, our culture, and our environment. The net effect, however, is a far-reaching shift in the dynamic between sellers of goods and providers of services, and those who purchase them. As consumers we are making new and different sorts of demands; we relate differently to brands; we expect to participate in determining what will be offered to us; and we expect our relationship with manufacturers and sellers to continue beyond the point of purchase. To meet these heightened expectations, companies have to yield some of their sovereign authority over

the market and enter into a two-way conversation with their customers. This shift is happening at three levels, and they will shape the argument of this chapter. First, there is a seemingly inexorable blurring of the line between “products” and “services,” as consumers shift from the expectation of functional performance to a more broadly satisfying experience. Second, design thinking is being applied at new scales in the move from discrete products and services to complex systems. Third, there is a dawning recognition among manufacturers, consumers, and everyone in between that we are entering an era of limits; the cycle of mass production and mindless consumption that defined the industrial age is no longer sustainable. These trends converge around a single, inescapable point: design thinking needs to be turned toward the formulation of a new participatory social contract. It is no longer possible to think in adversarial terms of a “buyer’s market” or a “seller’s market.” We’re all in this together.

Much has been written about complex nonhierarchical systems in which the behavior of the system is the result not of centralized command and control but of a set of individual behaviors that, when repeated thousands of times, achieve predictable results. Anthills and beehives are good examples, but when it comes to colonies of humans, we have to reckon with the additional factors of individual intelligence and free will (often to the despair of designers, police officers, and high school teachers). The implication is that we must think differently. Instead of an inflexible, hierarchical process that is designed once and executed many times, we must imagine how we might create highly flexible, constantly evolving systems in which each exchange between participants is an opportunity for empathy, insight, innovation, and implementation. Every interaction is a small opportunity to make that exchange more valuable to and meaningful for all participants.

Designers can’t prevent people from doing what they want to with products they own, but that does not excuse them from ignoring the larger system. Often, in our enthusiasm for solving the problem in front of us, we fail to see the problems that we create. Designers, and people who aspire to think like designers, are in a position to make important decisions about what resources society uses and where they end up. There are at least three significant areas where design thinking can promote what the Canadian designer Bruce Mau calls the “massive change” that is called for today. The first has to do with informing ourselves about what is at stake and making visible the true costs of the choices we make. The second involves a fundamental reassessment of the systems and processes we use to create new things. The third task to which design thinking must respond is to find ways to encourage individuals to move toward more sustainable behaviors.

The first two sentences is where I felt I was stuck in.

Chris Jordan is an American artist who uses the power of scale to connect us to many different social issues. His series Picturing Excess includes images such as a five-by-ten-foot representation of the number of plastic water bottles—about 2 million—consumed in the United States every five minutes. Another composition depicts 426,000 cell phones—the number retired by Americans every day. The visual impact of his work exposes our profligate use of the earth’s finite resources in a way that words cannot.

Another artist, the Canadian Edward Burtynsky, has traveled the planet recording the beauty and the horror of human impact.

...but design thinkers have also shown that it is possible to approach the challenge of sustainability at a more immediately accessible level. As director of the global foresight and innovation initiative at the engineering firm Arup, Dr. Chris Luebkeman created decks of cards he calls Drivers of Change. Each mutually reinforcing set covers a major category of environmental change—climate, energy, urbanization, waste, water, and demographics—with each card illustrating a single driver for change from a different perspective: society, technology, economics, environment, and politics. By means of imagery, graphs, and a few well-chosen facts, each card gives a clear picture of a single issue without overloading the viewer’s capacity to absorb and understand. One asks, “How important are trees?” and goes on to explain the issue of carbon emissions from deforestation. Another asks, “Can we afford a low carbon future?” and explains the impact of developing economies on carbon output. Arup uses Drivers of Change as a tool for discussion groups, as personal prompts, for workshop events, or simply as an inspirational “thought for the week.”

My next step, investigate the works of these three guys: Chris Jordan, Edward Burtynsky, Dr. Chris Luebkeman

We are in the midst of an epochal shift in the balance of power as economies evolve from a focus on manufactured products to one that favors services and experiences. Companies are ceding control and coming to see their customers not as “end users” but rather as participants in a two-way process. What is emerging is nothing less that a new social contract.

But those services and experiences require high-skilled workers. What do we do with all the others?Opportunities to rethink the structure of education exist all the way up the chain. Within the structure of a traditional art school, the California College of the Arts in San Francisco has applied the principles of design thinking—user-centered research, brainstorming, analogous observations, prototyping—to crafting its strategic plan for the future of arts education. The Royal College of Art in London is collaborating with its neighbor, the Imperial College, to leverage the different but mutually reinforcing types of creative problem solving found in art and engineering. In Toronto students at the Ontario College of Art & Design have the opportunity to team up with their counterparts at UT’s Rotman School of Management in a shared pursuit of creativity and innovation.

:: take a human-centered approach ::

Because design thinking balances the perspectives of users, technology, and business, it is by its nature integrative. As a starting point, however, it privileges the intended user, which is why I have consistently referred to it as a “human-centered” approach to innovation. Design thinkers observe how people behave, how the context of their experience affects their reaction to products and services. They take into account the emotional meaning of things as well as their functional performance. From this try to identify people’s unstated, or latent, needs and translate them into opportunities. The human-centered approach of the design thinker can inform new offerings and increase the likelihood of their acceptance by connecting them to existing behaviors. Asking the right kinds of questions often determines the success of a new product or service: Does it meet the needs of its target population? Does it create meaning as well as value? Does it inspire a new behavior that will be forever associated with it? Does it create a tipping point?

Like any good design team, we can have a sense of purpose without deluding ourselves that we can predict every outcome in advance, for this is the space of creativity. We can blur the distinction between the final product and the creative process that got us there. Designers work within the constraints of nature and are learning to mimic its elegance, economy, and efficiency, and as citizens and consumers we too can learn to respect the fragile environment that surrounds and sustains us. Above all, think of life as a prototype. We can conduct experiments, make discoveries, and change our perspectives. We can look for opportunities to turn processes into projects that have tangible outcomes. We can learn how to take joy in the things we create whether they take the form of a fleeting experience or an heirloom that will last for generations. We can learn that reward comes in creation and re-creation, not just in the consumption of the world around us. Active participation in the process of creation is our right and our privilege. We can learn to measure the success of our ideas not by our bank accounts but by their impact on the world.

This was a very good book. Inspiring. Innovative. Provocative. I learn more with each of these books I finish. It’s so amazing how all this information and guidance had fallen into my lap. It was always out there, but I didn’t see it until now. I thought I had information until I started this MFA process. I haven’t even scratched the surface.

art making:

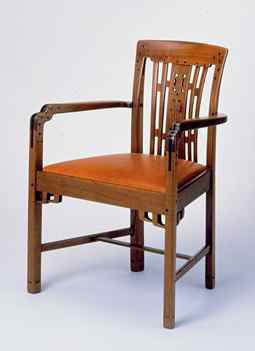

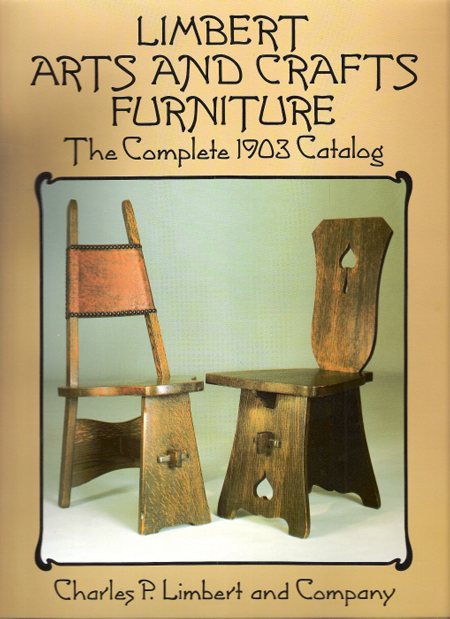

:: While researching and thinking about what drives me in this quest to fix everything, I was reminded of the Arts and Crafts Movement. This prompted a re-considering of my existing mark in light of shared viewpoints with the movement.Here are some of the early configurations and the final, new logomark for myself:

the final version:

Why the Arts & Crafts Movement turns me on

Simple form, beautiful proportions, the work tended to emphasize the qualities of the materials. It came about as a reaction against machine-production that tended to ignore materials and the basic design principles of beauty. Here’s an appropriate piece of text that I connect with (from Wikipedia):

::Social principles::

The Arts and Crafts philosophy was influenced by John Ruskin’s (1819–1900) social criticism, which sought to relate the moral and social health of a nation to the qualities of its architecture and design. Ruskin thought machinery was to blame for many social ills and that a healthy society depended on skilled and creative workers. Like Ruskin, Arts and Crafts artists tended to oppose the division of labor and to prefer craft production, in which the whole item was made and assembled by an individual or small group. They claimed to be concerned about the decrease of rural handicrafts, which accompanied the development of industry, and they regretted the loss of traditional skills and creativity.

Upcoming events I’ve attended or

will be attending:

:: AIGA Design Spectrum Series—Fabrica: Incubating the Modern Designer

Saturday, May 11—Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Established in 1994 in Treviso, Italy as Benetton’s communication research center, Fabrica is not a school or an advertising agency. Fabrica is an applied creative laboratory, a talent incubator, and a studio at which young modern artists from around the world develop innovative projects and explore new directions in a myriad of communication avenues. These artist-experimenters are accompanied along their research path by leading figures in art and communication, blurring the boundaries of culture and language and addressing a wide variety of social causes and disciplines.

:: Climate Change Series—University of Central MO

Part II: Thursday, May 30 - Dr. Paul Chambers, "Market Failure and Pollution"; 7:00pm, WC Morris Science Bldg;

Part III: Tuesday, June 4 -Dr. Kendy Hess, "Ethical/Political Considerations"; 7:00pm, WC Morris Science Bldg;

Part IV: Thursday, June 6 -Mike Shaw, "A Small Business Owner's Perspective", Malcolm Gavant, "An Industrialist's Point of View"; 7:00pm, WC Morris Science Bldg;

Part V: Tuesday, June 11 -Steve Mohler, "Conclusion: Where Do We Go From Here"; 7:00pm, WC Morris Science Bldg;

:: Maker Faire - KC

Saturday/Sunday, June 29 & 30—Union Station

Maker Faire: Kansas City celebrates things people create themselves — from new technology and electronic gizmos to urban farming and “slow-made” foods to homemade clothes, quilts and sculptures. This family-friendly event demonstrates what and how people are inventing, making and creating. It brings together Makers, Crafters, Inventors, Hackers, Scientists and Artists for a faire full of fun and inspiration. Come see what others are making and be inspired to tap into your own creativity!

still reading ::

Sacred Ecology - Fikret Berkes

Sacred Ecology - Fikret Berkes

:still reading/writing

reading ::

The Beginners Guide to Constructing the Universe: The Mathematical Archetypes of Nature, Art, and Science - Michael S. Schneider

The Beginners Guide to Constructing the Universe: The Mathematical Archetypes of Nature, Art, and Science - Michael S. Schneider

:: excerpts I found interesting:

I finished this just before first semester's end but didn't have time to insert content here

It's a great text!

Some Project Ideas I'm tossing around:

- Cistern revival—route water run-off from garage into old cistern, add a pump and use to water my garden

- Bottle passive solar nursery—use plastic bottle strung on wire framing and arched over a garden bed to insulate seedlings during the early spring days/nights. This would allow me to start the garden earlier.

- Mowing messages—I can mow forms in my front field that can be seen by passersby.

- Re-purposing sculptural—similarly to the mowing message, I’d like to construct with “the discarded”

- Solar power panel to add light or ventilation to one of my chicken houses.

- Wind turbine

- Algae

- Hydroponic gardening